Secondary Dominants: The Complete Guide

Learning Focus

Music Style

Free Lessons

Get free weekly lessons, practice tips, and downloadable resources to your inbox!

Do you like the sound of sophisticated chords on piano? You may not know what else to call them, but your ears certainly know that some chords are downright different…in the best possible way. Well, in today’s Quick Tip, Secondary Dominants: The Complete Guide, John Proulx shows you the secret to enhancing your piano playing with rich secondary dominant chords. You’ll learn:

- Intro to Secondary Dominants

- 5 Common Secondary Dominants You Should Know

- Secondary Dominant Chart for Quick Reference

- Using Secondary Dominants Chords in a Song

Intro to Secondary Dominants

Depending on your background and the type of music training you’ve had, you may or may not have heard of secondary dominants before happening upon today’s lesson. Without a doubt, some pianists who play by ear use these chords quite fluently without an awareness of the terminology for these particular sounds. On the other hand, some music majors vividly remember secondary dominants as a unit in freshman music theory for which they had to hire a tutor! Strangely, secondary dominants are sort of a harmonic paradox of music theory in that they are simultaneously advanced, yet simple.

Overview of Tonal Terminology

Before we get into a specific definition for the term secondary dominant, let’s first review some foundational terminology for the study of tonal music. For instance, we must know what the term dominant means, otherwise an explanation of “secondary” dominants will be of little help.

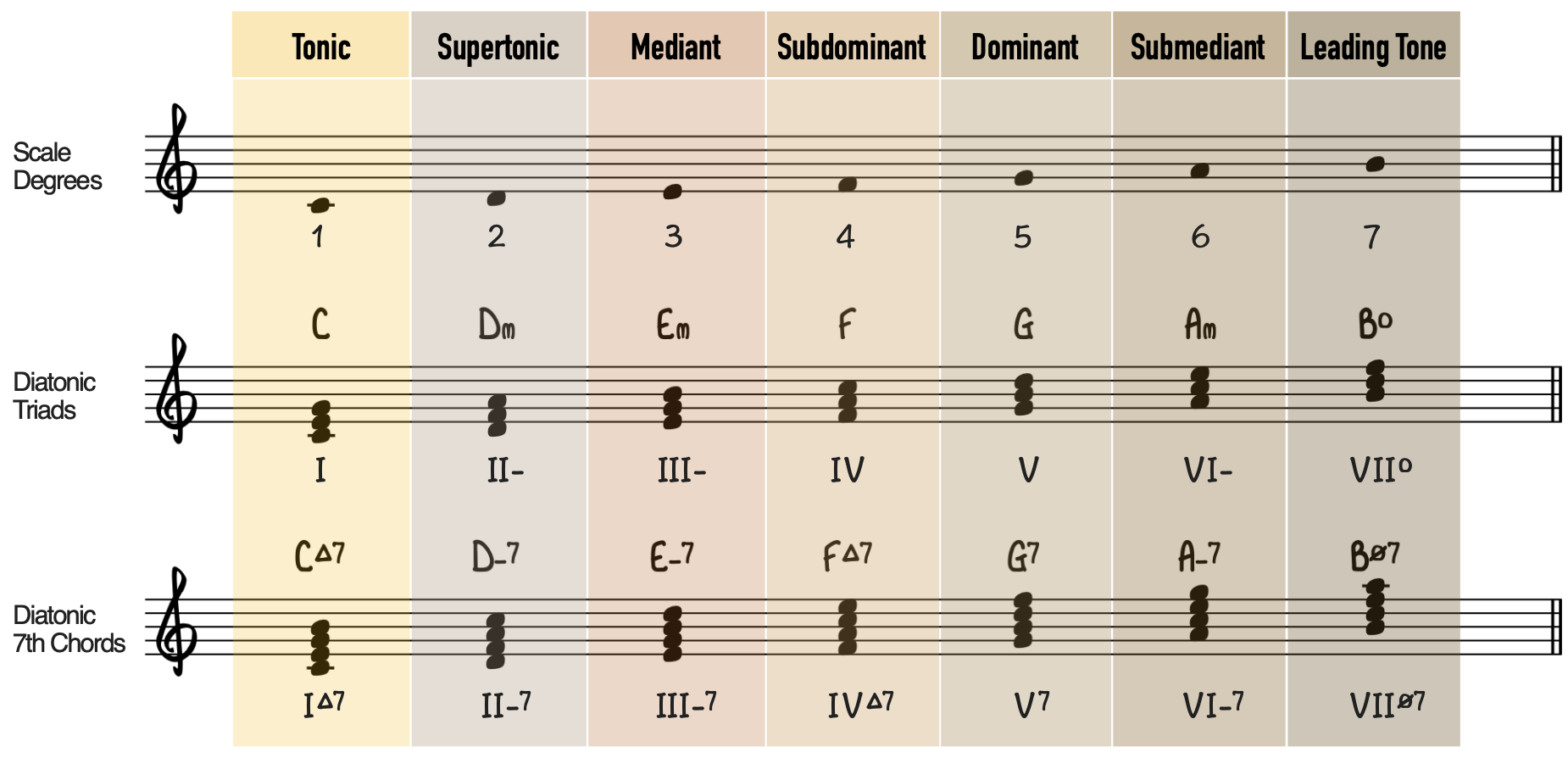

In music theory, the term dominant is simply the proper name given to the scale degree that is 5th above the tonic. Keep in mind, just like “tonic” can refer to either the first note of the scale or a chord built upon that note, in the same way, the term “dominant” is used to speak of the 5th scale tone as well as any chords built on that scale degree.

Generally speaking, the tradition in music theory is to use Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3, etc.) to refer to individual scale tones and Roman numerals (Ⅰ, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, etc.) to refer to chords. In addition, each scale degree and chord also has a proper name, as shown in the diagram below.

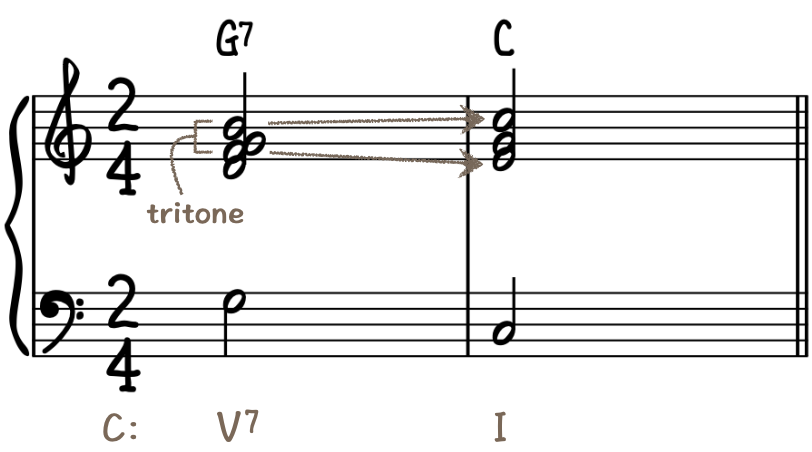

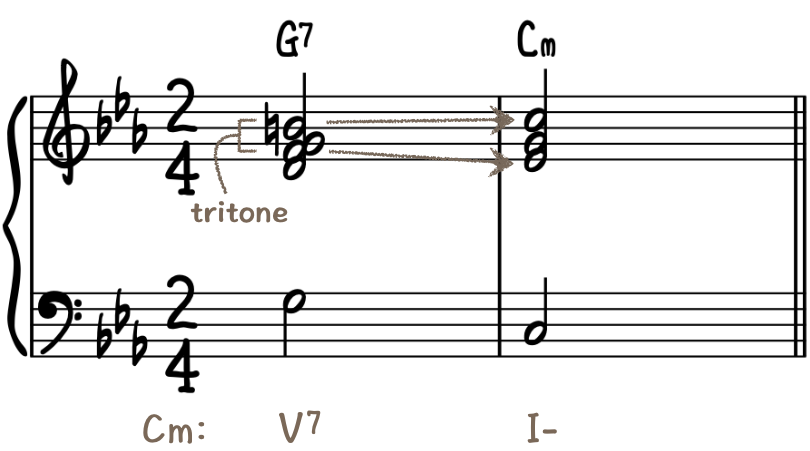

The dominant 7th chord (Ⅴ⁷) has a particularly unique function in tonal harmony. Firstly, it contains a palpable amount of internal tension because of the dissonance of tritone interval between its 3rd and 7th. In addition, the 3rd of the Ⅴ⁷ chord is the leading tone of the overall key, which has a strong inclination to resolve up a half step to the tonic. Similarly, the 7th of the Ⅴ⁷ resolves downward by stepwise motion to the 3rd of the tonic chord. Consequently, the chord progression of Ⅴ⁷ to Ⅰ results in a pleasing resolution, with a good balance of tension and release. The same effect is also true of Ⅴ⁷ to Ⅰ- in a minor key.

Now that we have a broad overview of some important terms, let’s take a closer look at the specific topic for today’s lesson.

What is a secondary dominant in music theory?

In music theory, a secondary dominant chord (aka applied dominant chord) is a harmonically expressive chord that behaves as a Ⅴ or Ⅴ⁷ chord and is used to resolve to a major or minor chord other than the tonic (i.e.: Ⅱ-, Ⅲ-, Ⅳ, Ⅴ, Ⅵ-). Thus, secondary dominants are a form of chromaticism, which requires the use of one or more accidentals (♯, ♭, ♮). In essence, a secondary dominant is a dominant chord from another key. As a result, secondary dominants have the sonic characteristics of a Ⅴ to Ⅰ resolution even though the target chord is not actually the Ⅰ chord. Examples of secondary dominants are Ⅴ of Ⅱ, Ⅴ of Ⅲ, Ⅴ of Ⅳ, Ⅴ of Ⅴ and Ⅴ of Ⅵ.

Virtually every musical genre employs secondary dominant chords to some extent. Just like regular dominant chords, secondary dominants may appear as major triads (Ⅴ), dominant 7th chords (Ⅴ⁷), extended dominant chords (Ⅴ⁹ or Ⅴ¹³), altered dominant chords (Ⅴ⁷♭9, Ⅴ⁷♯11, etc.) and suspended dominant chords (Ⅴ⁷sus⁴).

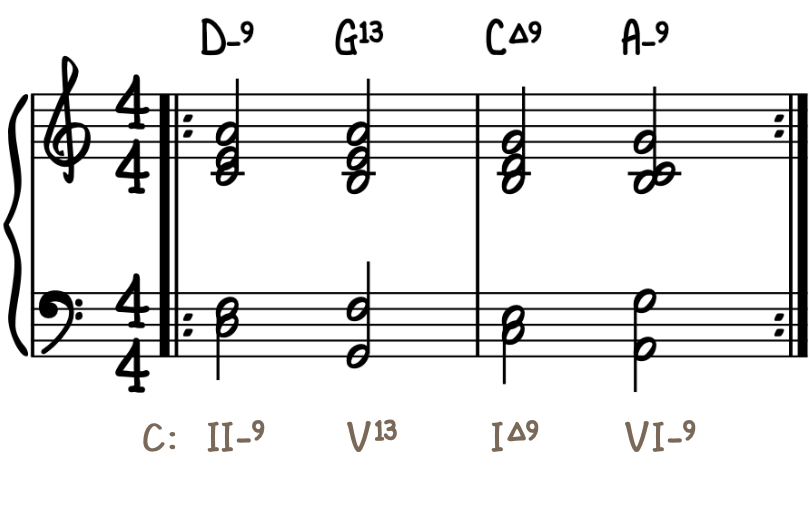

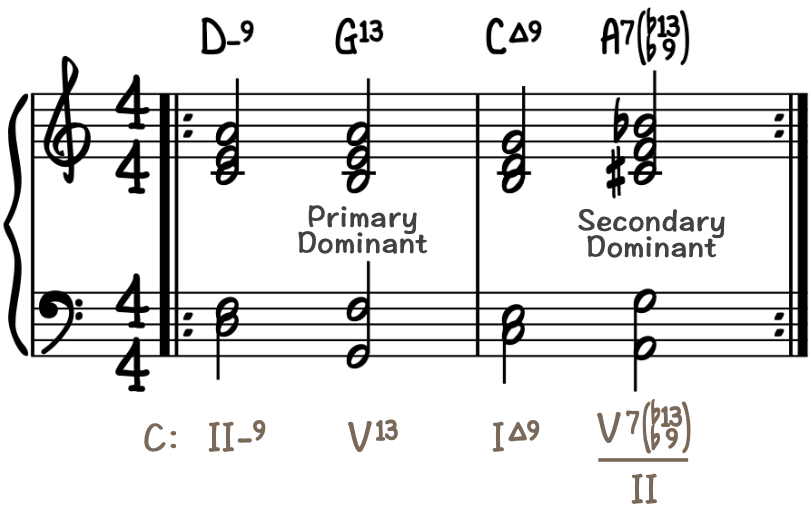

Let’s consider some sample chord progressions. Both of the following chord progressions are examples of the turnaround progression (Ⅱ→Ⅴ→Ⅰ→Ⅵ) in C major. In the first example, all of the chords are diatonic chords, and G¹³ is functioning as the dominant chord, which resolves to C▵⁹. In the second example, notice that there are two dominant chords: G¹³ and A7(♭9♭13). How are we to understand the chromaticism introduced by the A7(♭9♭13) chord? Is it arbitrary? Not at all. Notice, the A7(♭9♭13) resolves to D-⁹. This will sound just like a Ⅴ→Ⅰ- in the key of D minor…even though we haven’t left C major.

There are several different approaches for how to analyze secondary dominant chords. For starters, you might be inclined to assign the A7(♭9♭13) the Roman numeral Ⅵ⁷(♭9♭13). This label would not be wrong, but it doesn’t tell the whole story either. That’s because ordinarily, the submediant chord in a major key is not an altered dominant! Moreover, this particular Ⅵ chord is behaving much more like an altered Ⅴ⁷ chord, is it not? Therefore, another option would be to label A7(♭9♭13) as the Ⅴ⁷(♭9♭13) of Ⅱ. This latter approach reflects how the A7(♭9♭13) chord is actually functioning. Nevertheless, such an analysis is also rather cumbersome and requires quite a bit of space. Therefore, some musicians still prefer Ⅵ⁷ in this situation for the sake of a more concise analysis.

Hopefully, you’re beginning to get the big picture of how secondary dominants work. In the next section, you’ll get even more practice! You’ll also explore examples of secondary dominants in some familiar songs.

5 Common Secondary Dominants You Should Know

In this section, we’ll consider the 5 secondary dominants that are available in the key of C major, including real life examples from familiar songs. At the conclusion of this section, you’ll have a good indication of what secondary dominants sound like in a musical context. In fact, you’ll probably begin to recognize the sound of their complex harmonic character right away. Ultimately, the goal is to be able to discern-by-ear each specific secondary dominant that you hear.

In a major key, there are 5 secondary dominants that every musician should learn to recognize. They are:

Next, we’ll take a closer look at these chords one by one. But first, if you’re a PWJ member, be sure to download the lesson sheet PDF for today’s lesson. The download link for the lesson sheet appears at the bottom of this page after logging in with your membership. In addition, PWJ members can also easily transpose these examples to another key using our Smart Sheet Music.

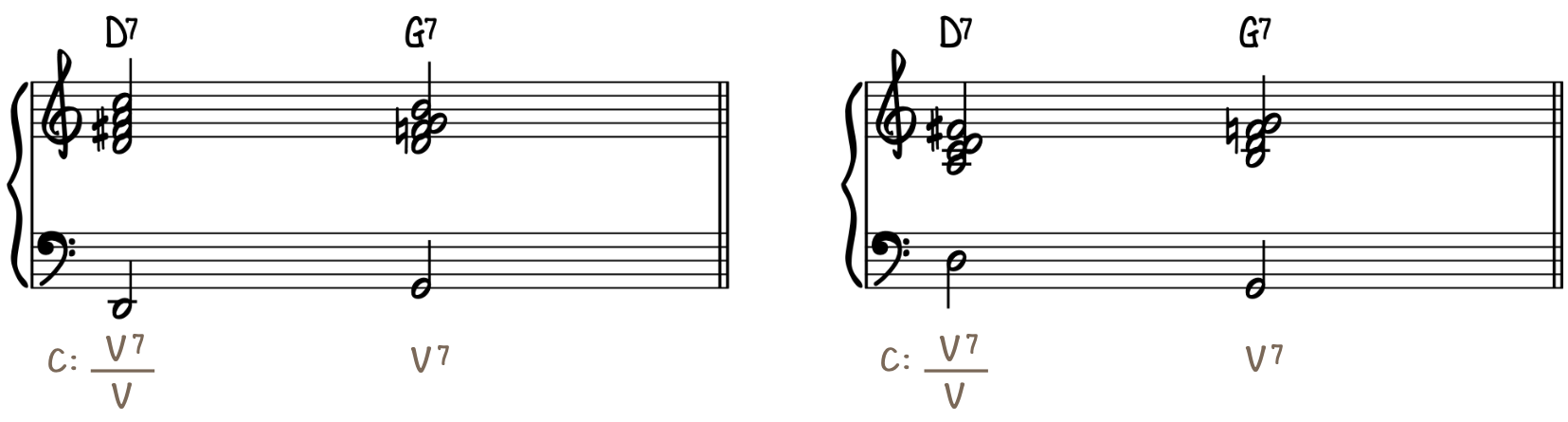

#1. The Ⅴ of Ⅴ

The first secondary dominant chord that we’ll consider is the Ⅴ of Ⅴ (pronounced as “five of five”). In C major, the diatonic Ⅴ chord is G major, or G⁷ if you add the 7th. To find the Ⅴ of Ⅴ, we need to go up a perfect 5th from the root of the Ⅴ chord. Following this process, we determine that a perfect 5th above G is the note D. Keep in mind, the diatonic chord built on D is a minor triad (D–F–A), which will not result in a dominant sound. At the very least, we must raise the 3rd of the chord to make it a D major triad (D–F♯–A). If we want more tension, we can add the 7th to create D⁷ (D–F♯–A–C). Depending on the musical genre, we could even add chord extensions and alterations. For now, we’ll just stick to dominant 7th chords.

At first glance, the Ⅴ⁷ of Ⅴ looks like a II⁷. However, if you see a II⁷ chord resolve to a Ⅴ chord, it’s a secondary dominant.

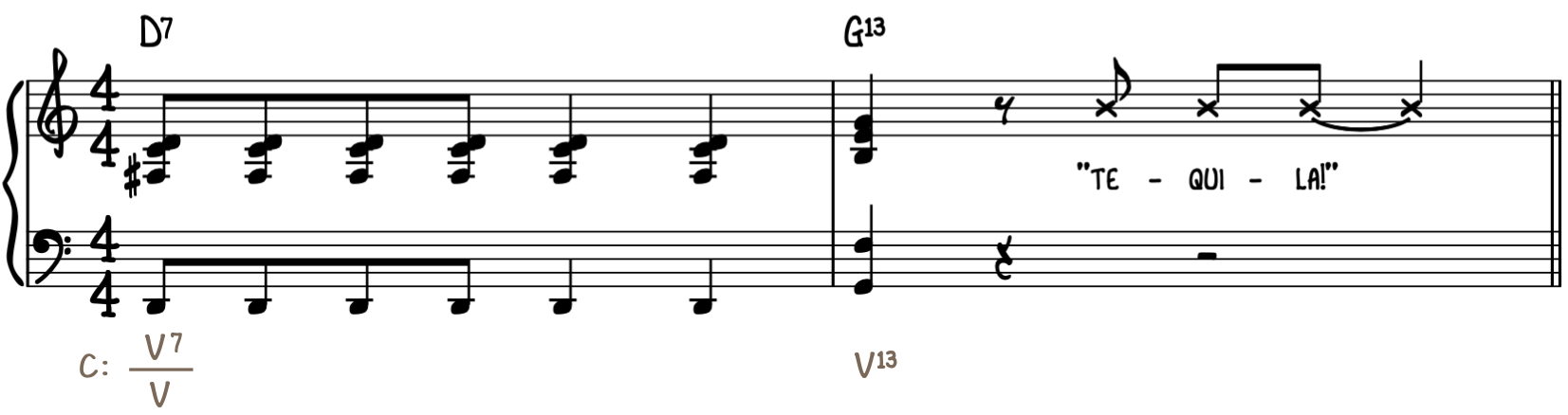

Ⅴ of Ⅴ Song Example: “Tequila”

The song “Tequila” (1958) by The Champs is example of a familiar song which contains the V⁷ of V at the end of the bridge section.

Next, let’s consider another very common secondary dominant that you’ll want to learn to recognize.

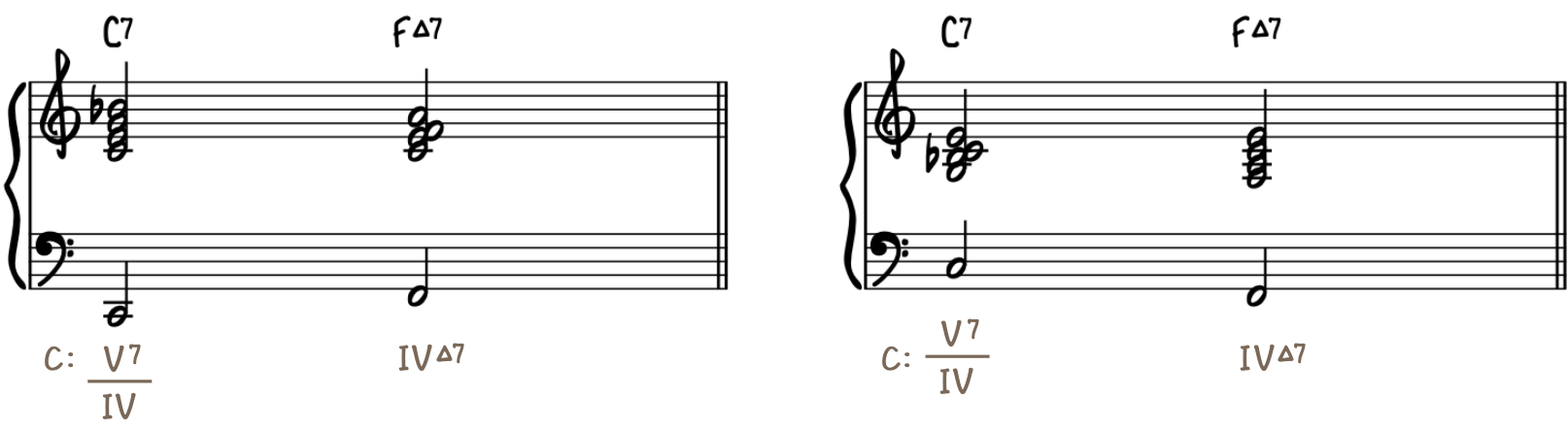

#2. The Ⅴ of Ⅳ

Another common secondary dominant is the Ⅴ of Ⅳ (pronounced as “five of four”). In C major, the diatonic Ⅳ chord is F major, or F▵⁷ if you add the 7th. In order to find the Ⅴ of Ⅳ, we need to go up a perfect 5th from the root of the Ⅳ chord. Using this process, we determine that a perfect 5th above F is the note C. Keep in mind, the diatonic chord built on C is our tonic chord—C major (C–E–G), which will not sound like a dominant chord without the addition of the minor 7th. Therefore, to create Ⅴ⁷ of Ⅳ, we use C⁷ (C–E–G–B♭).

In a major key, if you encounter what appears to be a Ⅰ⁷, it’s often functioning as the V⁷ of Ⅳ (except in the case of a blues tune).

Ⅴ of Ⅳ Song Example: “The Nearness of You”

The classic Great American Songbook standard “The Nearness of You” (1937) by Hoagy Carmichael and Ned Washington features the V⁷ of Ⅳ in the second full measure of the A section.

Let’s continue to discover another possibility.

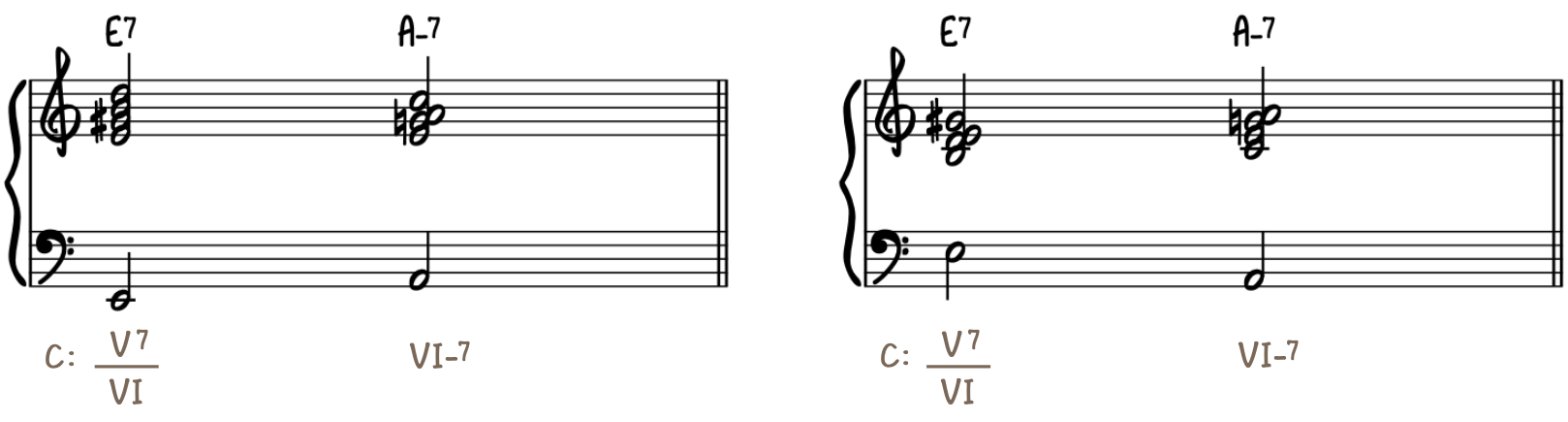

#3. The Ⅴ of Ⅵ

Yet another common secondary dominant is the Ⅴ of Ⅵ (pronounced as “five of six”). In C major, the diatonic Ⅵ chord is A minor, or A-⁷ if you add the 7th. To find the Ⅴ of Ⅵ, we need to go up a perfect 5th from the root of the Ⅵ chord. In doing so, we determine that a perfect 5th above A is the note E. Keep in mind, the diatonic chord built on E is a minor triad (E–G–B), which will not result in a dominant sound. At the very least, we must raise the 3rd of the chord to make it an E major triad (E–G♯–B). If we want more tension, we can add the 7th to create E⁷ (E–G♯–B–D).

In a major key, if you find what looks like Ⅲ⁷, check to see if it is functioning as the V⁷ of Ⅵ.

Ⅴ of Ⅵ Song Example: “Georgia On My Mind”

Another classic jazz standard by Hoagy Carmichael is “Georgia On My Mind” (1930), which features the secondary dominant Ⅴ of Ⅵ in bar two.

Ready for another? Next, let’s check out the Ⅴ of Ⅱ.

#4. The Ⅴ of Ⅱ

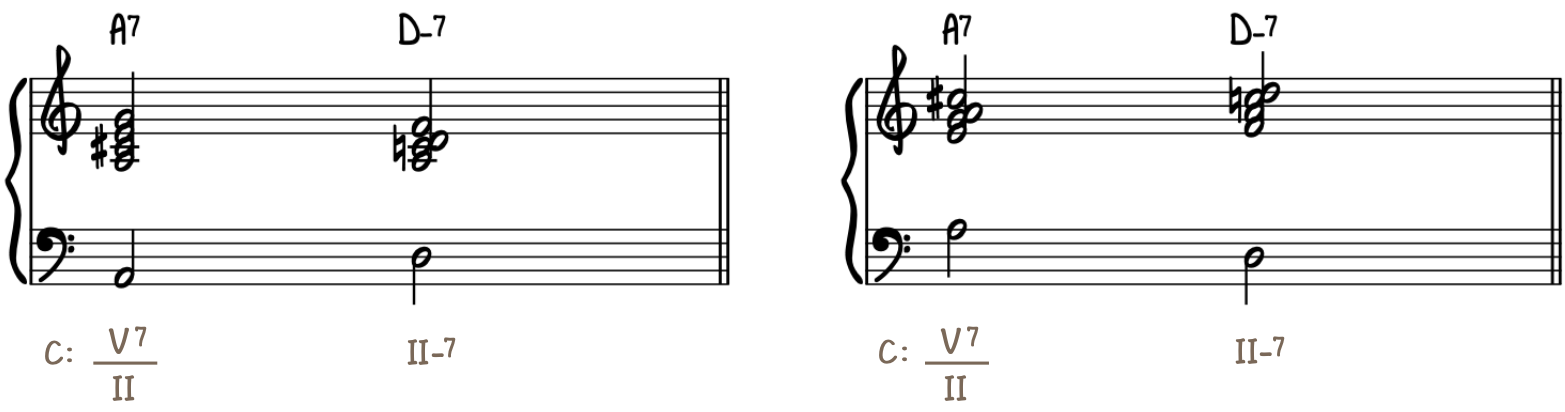

Still another common secondary dominant is the Ⅴ of Ⅱ (pronounced as “five of two”). In C major, the diatonic Ⅱ chord is D minor, or D-⁷ if you add the 7th. To find the Ⅴ of Ⅱ, we need to go up a perfect 5th from the root of the Ⅱ chord. Using this process, we recognize that a perfect 5th above D is the note A. Keep in mind, the diatonic chord built on A is a minor triad (A–C–E), which will not result in a dominant sound. At the very least, we must raise the 3rd of the chord to make it an A major triad (A–C♯–E). If we want more tension, we can add the 7th to create A⁷ (A–C♯–E–G).

In a major key, if you find what looks like Ⅵ⁷, check to see if it is functioning as the V⁷ of Ⅱ.

Ⅴ of Ⅱ Song Example: “Crazy”

The song “Crazy” (1961), which was written by Willie Nelson and popularized by Patsy Cline, is an example of a familiar song that contains the V⁷ of Ⅱ.

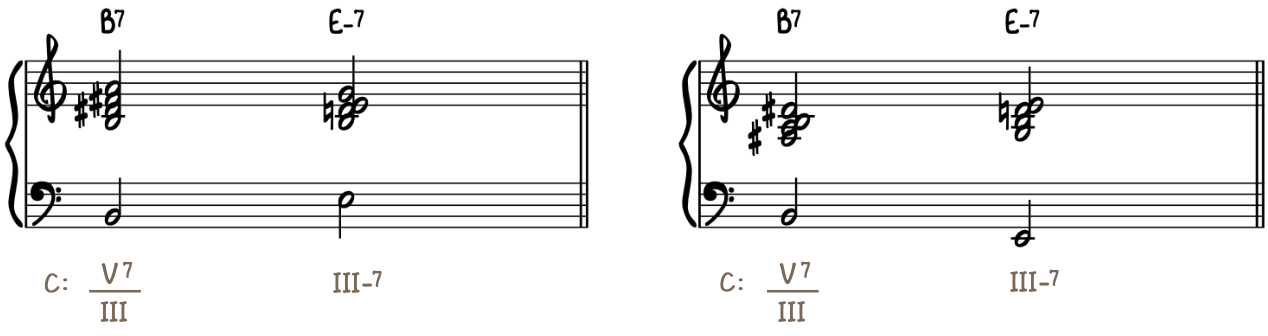

#5. The Ⅴ of Ⅲ

Finally, the last secondary dominant in a major key is the Ⅴ of Ⅲ (pronounced as “five of three”). In C major, the diatonic Ⅲ chord is E minor, or E-⁷ if you add the 7th. To find the Ⅴ of Ⅲ, we need to go up a perfect 5th from the root of the Ⅲ chord. Following this process, we realize that a perfect 5th above E is the note B. Keep in mind, the diatonic chord built on B is a diminished triad (B–D–F), which will not result in a dominant sound without some adjustment. At the very least, we must raise the 3rd and the 5th of the chord to make it a B major triad (B–D♯–F♯). If we want more tension, we can add the 7th to create B⁷ (B–D♯–F♯–A).

In a major key, if you find what looks like Ⅶ⁷, check to see if it is functioning as the V⁷ of Ⅲ.

Ⅴ of Ⅲ Song Example: “The Best Thing for You”

“The Best Thing for You” (1950) by Irving Berlin is a jazz standard that prominently features the V⁷ of Ⅲ.

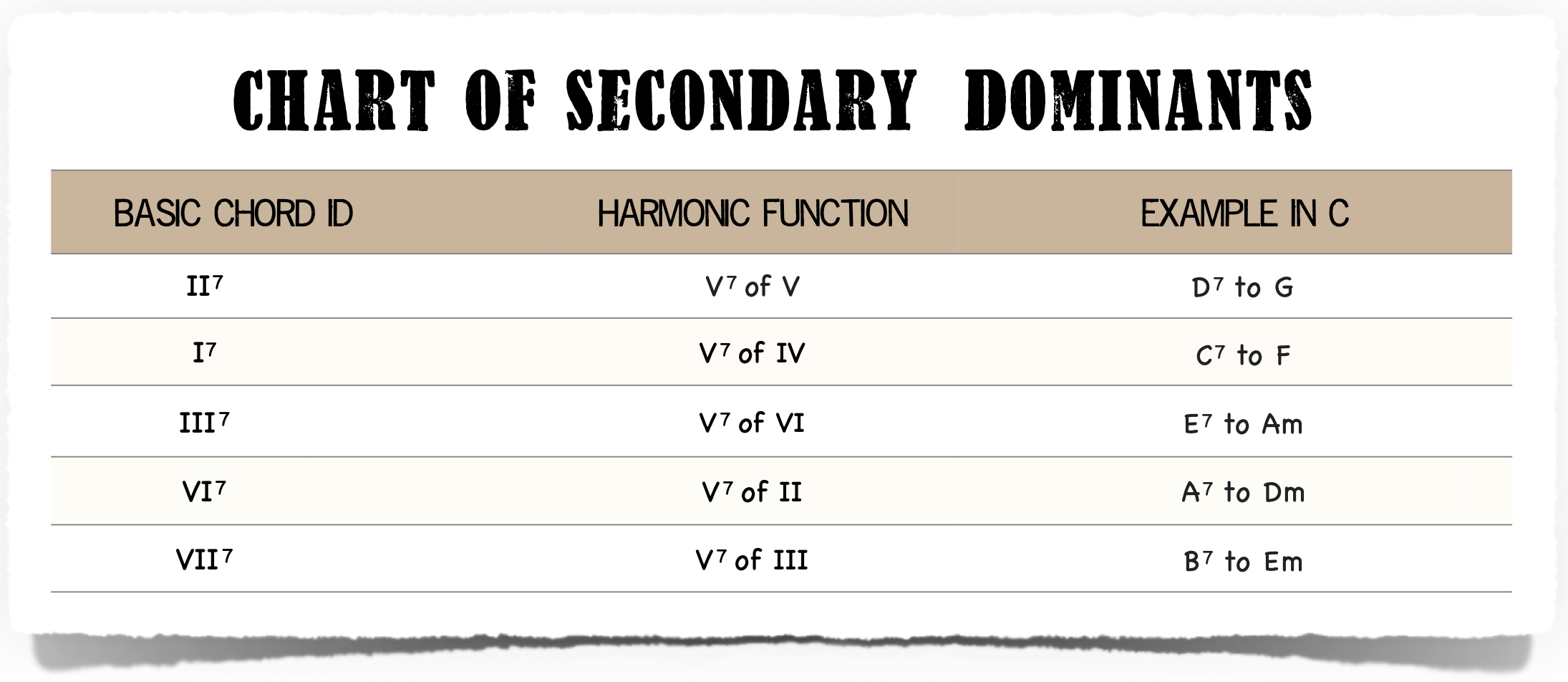

In the next section, we’ve included a helpful Secondary Dominant Chart that summarizes the 5 secondary dominants that are available in a major key.

Secondary Dominant Chart for Quick Reference

Secondary dominant chords are an important concept for all aspiring musicians to master. For instance, if you’re songwriter or an arranger, secondary dominants will keep your songs from sounding too diatonic. In addition, professional pianists use secondary dominants all the time to insert passing chords into pop standards, hymns, folk songs and holiday tunes.

The secret to adding secondary dominants to your playing is to memorize the relationship between each secondary dominant function and its basic chord ID. For instance, Ⅲ⁷ is the Ⅴ⁷ of Ⅵ, which is like E⁷→Am in the key of C major. This means that if you encounter a diatonic chord progression that contains Ⅲ- to Ⅵ- (Em→Am), there’s a good chance that the Ⅴ⁷ of Ⅵ will work quite well. All you have to do is change the Ⅲ- (Em) into Ⅲ⁷ (E⁷).

What if you see a progression that goes from Ⅰ to Ⅳ (C→F)? Why not try inserting the Ⅴ⁷ of Ⅳ (C⁷→F).

The following secondary dominant chart will help you identify and spot opportunities for adding secondary dominant chords.

In the next section, we’ll use secondary dominants to reharmonize the nursery rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb” with much more interesting chords.

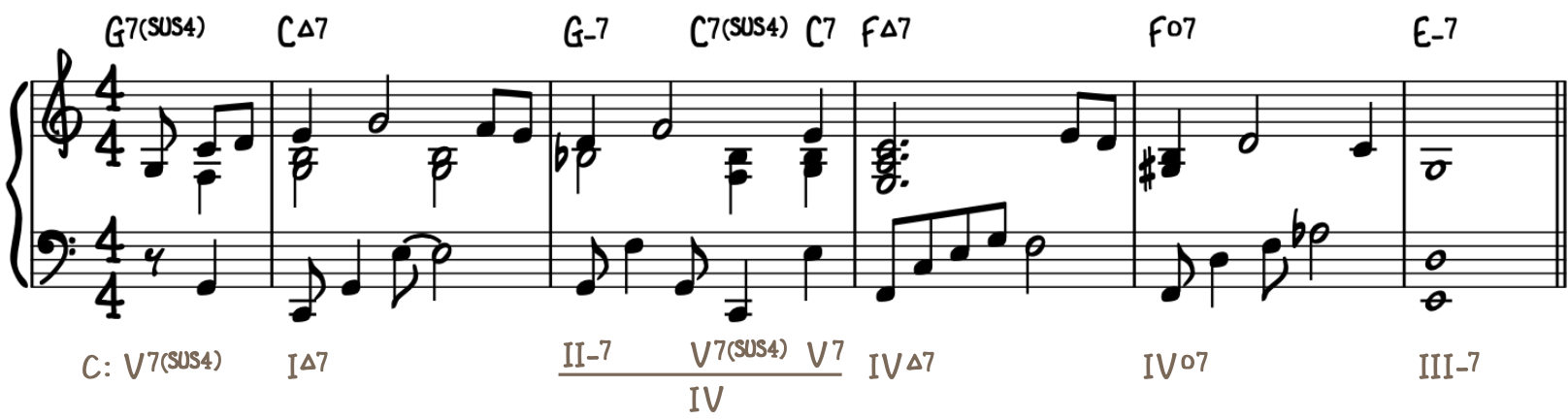

Using Secondary Dominants Chords in a Song

One of the benefits of learning music theory is that it allows you to personalize the music that you perform. In this section, we start with a basic version of “Mary Had a Little Lamb” and then transform it with secondary dominants.

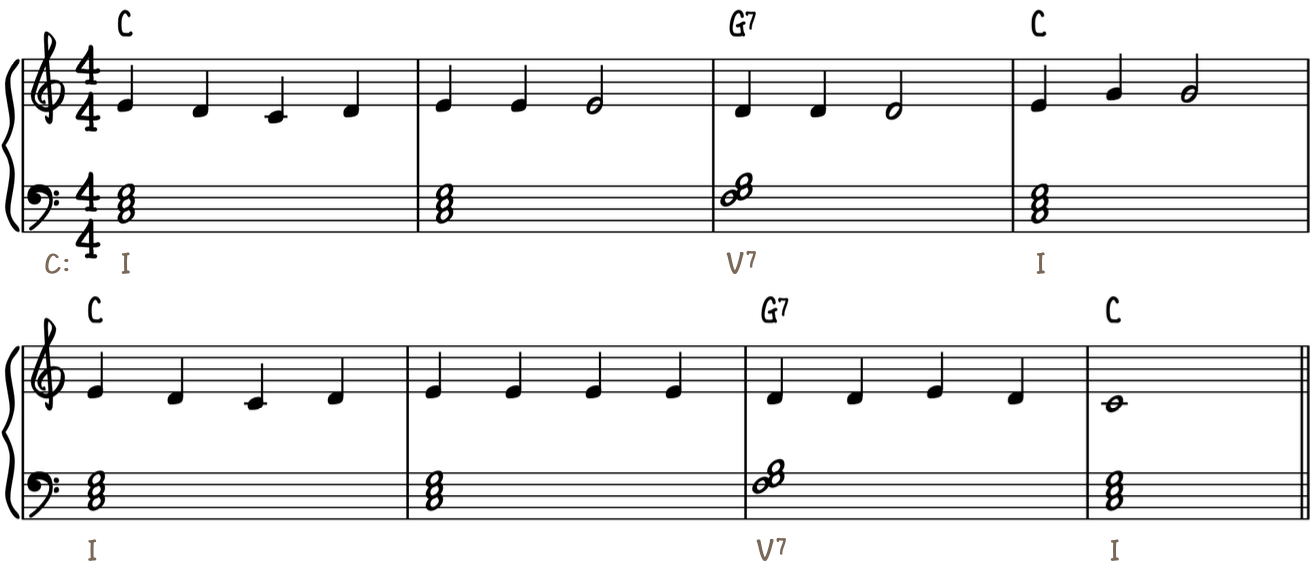

First, let’s examine the basic nursery rhyme as it would typically appear in a collection of folk songs. Notice, there are only two chord symbols…C and G⁷.

“Mary Had a Little Lamb” with Basic Chords

You could play it that way if you want to. However, you also have other options after mastering the secondary dominant techniques in today’s lesson. In fact, this tune is perfect for exploring reharmonization.

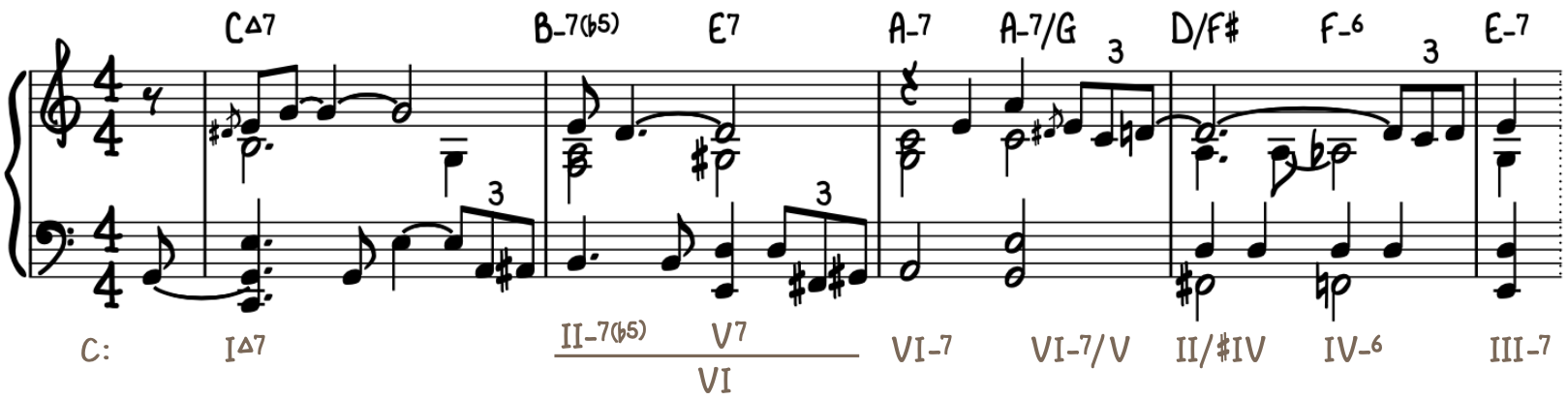

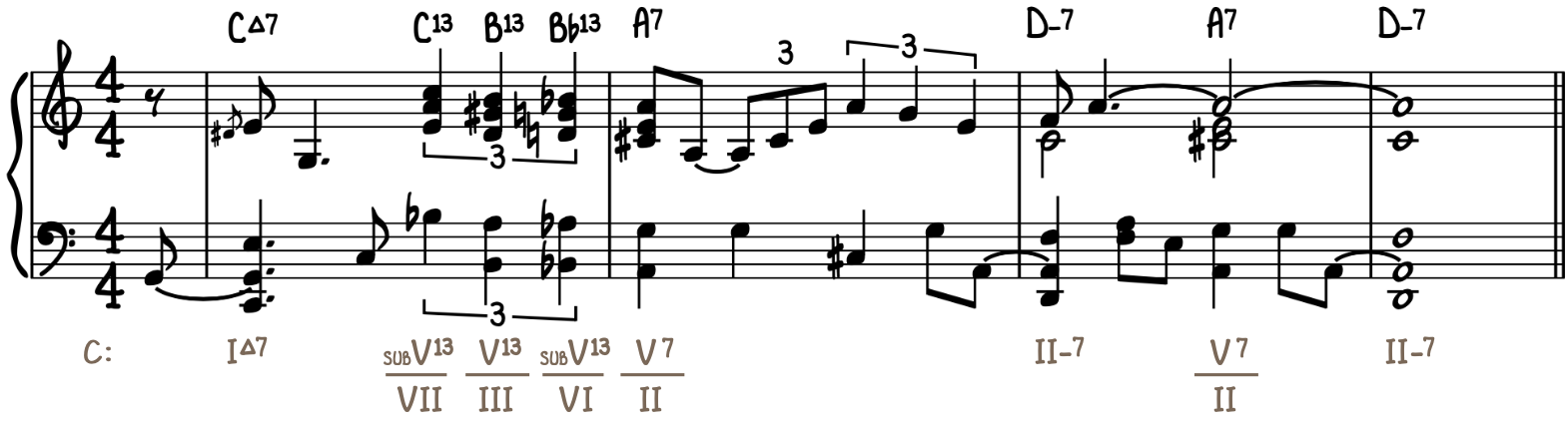

The following example is John Proulx’s reharmonization of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.” Check it out…

“Mary Had a Little Lamb” with Secondary Dominants

Wow, those are some beautiful and sophisticated sounding chords! Believe or not, this example represents just one possibility. The sky is the limit!

Conclusion

Congratulations, you’ve completed today’s lesson on Secondary Dominants: The Complete Guide. With the harmonic insights you’ve gleaned in today’s lesson, you’ll be able to approach familiar tunes with brand new harmonic possibilities!

If you enjoyed today’s lesson, then be sure to check out the following PWJ resources:

Courses

- Passing Chords & Reharmonization (Int, Adv)

- Piano Chord Extensions (Int)

- Piano Chord Alterations (Int)

- Coloring Dominant Chords with Upper Structures (Adv)

- 6 Jazz Ballad Harmonic Approaches (Int, Adv)

- Jazz Standard Analysis (Int, Adv)

- Danny Boy (Adv)

- Over the Rainbow Challenge (Beg, Int, Adv)

- Amazing Grace Piano Hymn–Slow Gospel Blues (Int, Adv)

Quick Tips

- 3 Steps to Make Your Piano Chords More Interesting (Int)

- Passing Chords: 5 Levels (Beginner to Pro)

- 10 Ways to Spice Up a Simple Piano Chord Progression (Int)

- Modal Interchange: The Complete Guide to Borrowed Chords (Int)

- Reharmonization: Play Any Note with Any Chord (Int/Adv)

- Chord Extensions – The Complete Guide (Int)

- Create Inner Voice Movement for Jazz Piano (Int)

- Sus Chords for Piano: The Ultimate Guide (Int)

Piano Foundations Learning Tracks

Theory & Analysis Learning Tracks

Thanks for learning with us today! We’ll see you next time.

Would you like to comment on this lesson?

Visit this Quick Tip on YouTube

Writer

Writer

Michael LaDisa

Michael LaDisa graduated from the University of North Texas with a major in Music Theory & Composition. He lives in Chicago where he operates a private teaching studio and performs regularly as a solo pianist. His educational work with students has been featured on WGN-TV Evening News, Fox 32 Good Day,...

More Free Lessons

I'll show you the formulas that I use the play any song in any style. It's easier than you probably think!

If you're practicing scales the old fashioned way, and you want to play jazz, there is a much better way!

There is one main reason why students don't like their solos, and when you realize this, you'll know exactly what to fix.

Looking for downloads?

Subscribe to a membership plan for full access to this Quick Tip's sheet music and backing tracks!

Join Us

Get instant access to this Quick Tip and other member features with a PWJ membership!

Guided Learning Tracks

View guided learning tracks for all music styles and skill levels

Progress Tracking

Complete lessons and courses as you track your learning progress

Downloadable Resources

Download Sheet Music and Backing Tracks

Community Forums

Engage with other PWJ members in our member-only community forums

Become a better piano player today. Try us out completely free for 14 days!