“The Lick” Jazz Meme: The Complete Guide

Learning Focus

Music Style

Free Lessons

Get free weekly lessons, practice tips, and downloadable resources to your inbox!

Have you ever been to a jazz show and heard “The Lick?” You know, that short musical phrase that has been used so much that it has become a jazz meme—a type of inside joke between jazz musicians. Well, all joking aside, in today’s Quick Tip, “The Lick” Jazz Meme—The Complete Guide, John Proulx mulls over this overused phrase with a creative lens to discover new musical possibilities. You’ll learn:

- Introduction to “The Lick” Jazz Meme

- Variations on “The Lick”

- Harmonization: What chords work with “The Lick?”

- Transpose and Play “The Lick” in All 12 Keys

Today’s lesson demonstrates that with a bit of rhythmic and harmonic imagination, you can breath new life into any musical phrase.

Introduction to “The Lick” Jazz Meme

Many of you are already familiar with “The Lick.” You know the one…🎶 Doo ba dih bee Dwee, doo dahhh 🎶. For those on the outside, however, the joke needs to be explained.

What is “The Lick” and why is it so popular?

“The Lick” is a seven-note musical phrase that occurs in jazz and pop music with such frequency that it has been dubbed “the most famous jazz cliché ever.”¹ In the modern era of social media, “The Lick” has become an internet meme that has spread with vast proliferation.

Even though you might get the “side-eye” from your bandmates for using “The Lick” on the bandstand, many well-respected jazz musicians have used this bit of collective jazz vocabulary in their improvisations. The short list includes Chet Baker, Freddie Hubbard, Charlie Parker, John Coltrane, Dexter Gordon, Pat Metheny, Kieth Jarrett, Chic Corea, Herbie Hancock and Bobby Hutcherson. “The Lick” has also frequently appeared on mainstream pop and R&B records by artists including Carlos Santana, Christina Aguilera, Usher, D’Angelo and Adriana Evans—even reggae artist Bob Marley.

“The Lick” Original Compilation

Alex Heitlinger (2011)

Memefication of “The Lick” Timeline

If you are late to the party (or even if you are not), you can casually peruse the timeline below to relive some key hilarious moments in the memefication of “The Lick” over the past decade. After a few minutes, you’ll be in on the joke too!

- 2010 – Dedicated Facebook page for “The Lick” where users share sightings

- 2011 – Jazz composer Alex Heitlinger posts “The Lick” video compilation on YouTube

- 2013 – New York Jazz Academy “The Lick in All 12 Keys”

- 2015 – Antonie Beaudet’s “Fugue on The Lick”

- 2017 – Adam Neely plays “The Lick for 5 Hours Straight”

- 2017 – “The Lick” arrives on Reddit forming another internet community for sharing appearences

- 2018 – NYJA “The Lick” Infographic—”All I Really Need to Know About JAZZ, I Learned from THE LICK”

- 2019 – David Bruce composes “The Lick” Quartet

- 2022 – InstrumentManic Luke Pickman’s “The Lick on 91 Instruments”

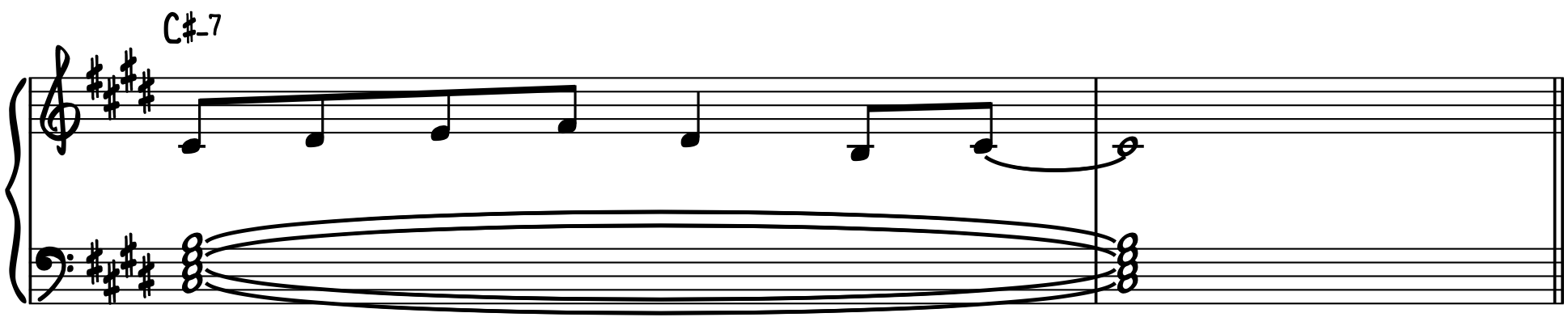

What are the notes to “The Lick?”

To play “The Lick” starting on any note, use the following formula: 1–2–♭3–4–2–♭7–1. For example: D–E–F–G–E–C–D. Rhythmically speaking, the phrase is generally expressed in 4/4 time using four 8th notes, 1 quarter note and 2 more 8th notes (♫♫♩♫). The final 8th note is usually tied to a longer note value in the subsequent measure. In addition, players will often ornament the quarter note with a grace note or “scoop.”

Where did “The Lick” come from?

Licks, in general, are short recognizable musical phrases shared within music communities. Determining who played “The Lick” first is as difficult as investigating who was the first person to tell a particular joke. Notwithstanding, “The Lick” can be found as early as 1910 in Russian composer Igor Stravinsky’s Firebird.

“Licks are generally not owned…they function as a grey area between inspiration and infringement…they can be exchanged between musicians freely.”

—Hannah Judd, Ethnomusicologist

Composer and author Andrew Durkin writes, “Most musicians intuitively understand that music in general relies on an abundance of shared licks, rhythms, lyrical phrases, and chord progressions.”² Furthermore, ethnomusicologist Hannah Judd points out that “they are pre-melodies – short, stock melodic phrases that are exchangeable, and therefore mutable, which act as building blocks for a solo. Licks are generally not owned…they function as a grey area between inspiration and infringement, where, short enough, in different contexts, they can be exchanged between musicians freely.”³

Dig That Lick: Online Audio Database of Melodic Patterns in Jazz Performance

This concept of a collective, communal jazz vocabulary is well researched and documented. Even though we can’t say for certain who played “The Lick” first, we can certainly say who has played it, and when. If fact, thanks to Dig That Lick, a cooperative project between six universities across four countries, we can quite easily search a large online database of jazz audio excerpts compiled by musicologists and computer scientists.

Common Variations of “The Lick”

So far, we have covered many background considerations concerning “The Lick.” Now, let’s get to some actual playing by examining the most common variations of “The Lick” that you’re likely hear. First, be sure to download the complete lesson sheet PDF and backing tracks for today’s lesson from the bottom of this page after logging in with your membership. In this section, we’ll play “The Lick” starting on the note B. However, PWJ members can easily transpose the lesson material to any key using our Smart Sheet Music.

The 7 examples below allow you to easily compare and contrast different ways in which “The Lick” is often expressed, including:

- Stock Version: the lick in its essential form.

- Expanded Chord Outline: scale degree 5 can be added before the final note; this note is often played softly, or “ghosted,” in performance.

- Slide Ornament: the 5th note often is often approached with an ornament that can be described as a slide, grace note, scoop or bend. The slide can be a whole step or a ½ step depending on the genre.

- Turn Ornament: a turn ornament is common between the 5th and 6th notes.

- Upper Harmony: added coloration can be created by adding harmony above the melody; upper harmony is often combined with slides (aka harmonized slides).

- Pickup Note: many players add a pickup note (aka anacrusis) that is a perfect 4th below the first note.

- Rhythmic Displacement: notes can be shifted earlier or later along rhythmic grid by elongating one or more notes, repeating notes or by adding rests. The most common rhythmic variations involve syncopations created by 8th note displacement, such as Santana’s “Oye Como Va” lick shown in example 7.

1. Stock Version

2. Expanded Chord Outline

3. Slide Ornament

4. Turn Ornament

5. Upper Harmony

6. Pickup Note

7. Rhythmic Displacement

Now that you’ve learned several different ways to express the lick melodically, let’s look at how the lick can be approached harmonically.

Harmonization: What chords work with “The Lick?”

Many working musicians have come to loathe the “The Lick” due to its pervasiveness, which is often excessive and unoriginal. However, it does possess an appealing melodic syntax that makes it a legitimate piece of improv vocabulary still used by professional musicians, albeit rather sparingly.

In this section, we’ll examine various harmonic relationships that you can use to harmonize “The Lick” in ways that are significantly more earthy and organic than you’re likely to hear at a middle school band concert.

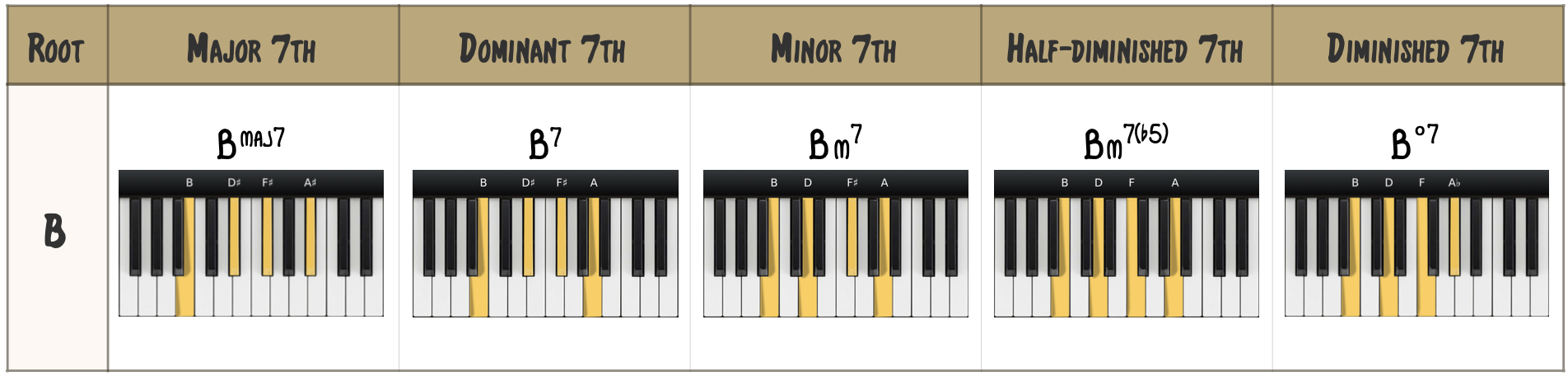

John Proulx’s method for harmonizing “The Lick” follows a simple formula that you can apply to many other situations. First, harmonize “The Lick” by treating its initial note as the root of the chord. Next, reharmonize the phrase by treating its initial note as the 3rd of the chord. Repeat this process by treating the initial note as the 5th of the chord and the 7th of the chord. Determining whether the supporting chord should be major, minor or otherwise requires a bit of harmonic fluency. Essentially, you must determine the chord quality by considering not only the initial note, but all of the other notes as well. Taken as a whole, the notes will imply a particular chord quality.

Starting on the Root

Let’s look at the first scenario. Since we’re still examining “The Lick” beginning on the note B, the first and simplest harmonization is to treat B as the root of the chord. Next, try to determine which chord quality containing B as the root is the “best fit” for all of the notes: B–C#–D–E–C#–A–B.

For example, can you see that Bmaj7 (B–D#–F#–A#) does not fit with these notes? Instead, Bm7 (B–D–F#–A) is a perfect fit. In the following example, John uses a hip Bm9 rootless voicing which sounds fantastic. In addition, John includes a C#m9 passing chord between subsequent iterations of “The Lick.” This passing chord technique called chord planing.

Great job, you’re ready to try the next example.

Starting on the 3rd

Next, we want to play “The Lick” with the exact same pitches, B–C#–D–E–C#–A–B, but we want to harmonize it with a different chord altogether. To accomplish this, we’ll treat the initial note B as the 3rd of the supporting chord. Drawing on the diatonic chords from B natural minor, the chord that contains the note B as the 3rd is Gmaj7. In the example below, John has voices this chord with a Gmaj9 rootless voicing.

As you can hear, this reharmonization has a very hip effect, similar to changing the filter on a photo. (Note, the root of Gmaj9 is a minor 6th interval above the tonic note B. The analysis above expresses this chord as ♭VImaj9 to indicate that G is the lowered 6th scale degree. In some respects, the “♭” here is cautionary since G is already natural (♮) according to the key signature. Therefore, an analysis of VImaj9 is also valid as long as the key signature does note contain a G♯.)

Starting on the 5th

Next, we’ll treat the initial note B as the 5th of a diatonic chord in B minor. The chord that correspondes to this scenario is Em7, which is notated below with an Em9 rootless voicing. This chord is IVm9 in the key of B minor.

Starting on the 7th

Lastly, we can treat the initial note B as the 7th of the chord. In this case, you might be tempted to play Cmaj7 (C–E–G–B). However, the note C# in “The Lick” conflicts with Cmaj7. Instead, we’ll use C♯7alt. Even though C♯7alt is not native to B minor, this chord is still a strong fit because all of the notes in “The Lick” fit within the C# Altered Scale: C#–D–E–F–G–A–B. This chord’s function is II7alt.

Sometimes, more than one chord will work. For example, C♯ø7 also fits here for as the diatonic IIø7 in B minor. However, the crunchy sound of that II7alt is hard to resist!

Notice that “The Lick” also ends on the note B as a whole note. In the next section, we will actually use Cmaj7 as passing chord during this whole note to slide back down into Bm7 and repeat the entire chord progression (Im9→♭VImaj9→IVm9→II7alt).

Putting It All Together

In the previous section, we followed a formulaic process to harmonize the lick in B minor over 4 unique chord functions. As a result, we came up with the chord progression Im9→♭VImaj9→IVm9→II7alt, or Bm9→Gmaj9→Em9→C#7alt.

In today’s Quick Tip video lesson, John Proulx demonstrates how to apply additional reharmonization techniques to expand this chord progression into a complete smooth jazz song form. Check it out:

Now that’s a treatment of “The Lick” that’s worth repeating! To learn more about how to use passing chords, check out our full-length courses on Passing Chords & Reharmonization (Inv, Adv)

Transpose & Play “The Lick” in All 12 Keys

As an improviser, a great way to develop fluency on your instrument is to transpose musical ideas into all 12 keys. Ideally, you want to be able to do this without the need to see the phrase written out in music notation. However, many students initially need to write out a passage in several keys before they are comfortable completing the transposition mentally. Here are a few common methods that jazz musicians use to cover all 12 keys:

- Counter-clockwise around the Circle of 5ths

- Chromatically ascending or descending

- Ascending or descending by whole steps

- Ascending or descending by minor 3rds

For most players, the easiest method for mental transposition is to ascend chromatically. Therefore, we’ve arranged the following examples in an ascending chromatic sequence for your convenience.

C Minor

C♯ Minor

D Minor

E♭ Minor

E Minor

F Minor

F♯ Minor

G Minor

A♭ Minor

A Minor

B♭ Minor

B Minor

Conclusion

Congratulations, you’ve completed today’s lesson on The Lick Jazz Meme—The Complete Guide. Without a doubt, you have gained additional perspective on this bit of ubiquitous jazz vocabulary.

If you enjoyed today’s lesson, then you’ll love the following PWJ resources:

Quick Tips

Learning Tracks

Would you like to comment on this lesson?

Visit this Quick Tip on YouTube

² Durkin, Andrew. Decomposition: A Musical Manifesto, Pantheon Books, New York, 2014, pp. 257.

Writer

Writer

Michael LaDisa

Michael LaDisa graduated from the University of North Texas with a major in Music Theory & Composition. He lives in Chicago where he operates a private teaching studio and performs regularly as a solo pianist. His educational work with students has been featured on WGN-TV Evening News, Fox 32 Good Day,...

More Free Lessons

Some jazz standards like “On Green Dolphin Street” mix Latin and swing within the same song…Learn how to master these “transition tunes.”

Learn to play in the exhilarating rock and roll piano style of Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis—including grooves, chords, licks and riffs.

Explore the methods and mindset needed to comp on piano in the swing style with this complete guide to jazz piano comping for all levels.

Looking for downloads?

Subscribe to a membership plan for full access to this Quick Tip's sheet music and backing tracks!

Join Us

Get instant access to this Quick Tip and other member features with a PWJ membership!

Guided Learning Tracks

View guided learning tracks for all music styles and skill levels

Progress Tracking

Complete lessons and courses as you track your learning progress

Downloadable Resources

Download Sheet Music and Backing Tracks

Community Forums

Engage with other PWJ members in our member-only community forums

Become a better piano player today. Try us out completely free for 14 days!