Playing Solo Jazz Piano With Jeremy Siskind

Learning Focus

Music Style

Free Lessons

Get free weekly lessons, practice tips, and downloadable resources to your inbox!

In this interview, Jonny talks with award-winning pianist, composer and author Jeremy Siskind on the three elements of solo jazz piano playing. PWJ members can view the full interview here.

Pianist-composer Jeremy Siskind is a two-time laureate of the American Pianists Association and the winner of the Nottingham International Jazz Piano Competition. Since making his professional debut juxtaposing Debussy’s Etudes with jazz standards at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Hall, Siskind has established himself as one of the nation’s most innovative and virtuosic modern pianists.

A highly-respected educator, Siskind teaches at California’s Fullerton College, chairs the National Conference for Keyboard Pedagogy’s “Creativity Track,” and spreads peace through music in places like Lebanon, Tunisia, and Thailand with the non-profit organization, Jazz Education Abroad. Jeremy Siskind is a Yamaha artist.

This is a guest blog post by Jeremy Siskind

I was so grateful to have the chance to chat with the great Jonny May recently, and especially happy to talk about my passion, playing solo jazz piano.

To me, solo jazz piano is one of the most honest artforms out there. Solo jazz pianists have the awesome potential to express themselves through music with absolute directness and freedom. Without the constraints of either a band or sheet music, solo jazz pianists are limited only by our own technique and imagination.

But playing solo jazz piano is also incredibly tricky. With only two hands, solo pianists are expected to express three musical elements – melody, chords, and bass. If any of these elements are missing, the resulting performance might be thin, rhythmically bland, or stylistically compromised.

Generations of pianists have explored different ways of accommodating the three elements with two hands, and I’d like to summarize some of the most important approaches here.

Playing Solo Jazz Piano: Stride Piano

In stride piano, the left hand takes the bass and chords while the right hand covers the melody. It’s said that stride piano was born out of the need to play solo piano arrangements of brass band hits (think John Philip Sousa) which frequently found the tubas and euphoniums playing bass notes on the strong beats (one and three), while the French horns played the mid-range chords on the weak beats (two and four). In order to accommodate both parts, the pianist’s left hand has to quickly “stride” back and forth every beat. Stride piano and ragtime are similar, but the difference is more philosophical. Ragtime is fully written-out music whereas stride piano is largely improvised and open-ended.

There’s an almost mind-blowing amount of variation possible with stride piano. In fact, I wrote four whole chapters about stride piano in my recent book, Playing Solo Jazz Piano.

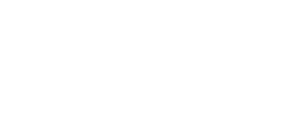

You can change the stride pattern (that is, the alternation of bass-chord-bass-chord), anticipate some of the beats, add walking tenths and skip beats, bolster the bass and the chord with color tones, and even create rhythmic variety with the pedal. Here’s a brief example of what stride can look like in the “real world:”

STRIDE STYLE COMPING

“Comping,” short for “accompanying” or “complementing,” is a word used to describe how jazz pianists play chords. In stride-style comping, the left hand still covers both the bass and chords, but instead of playing every beat, like it does in stride piano, it spreads out the elements to create a more unpredictable, syncopated accompaniment.

When you listen to professionals comp, it generally sounds unpredictable and almost “random.” Yes, we want to aim to have that much variety in our comping. However, as students, we have to learn to walk before we can run. I start my students with three traditional comping patterns, and then we learn ways to mix between them and ornament them. They are:

The Charleston

The Reverse Charleston

Red Garland Pattern

When you’ve mastered these patterns, you can add ornaments in the bass to fill in empty spaces and have more of a “conversation” between left hand and right hand. Below is a Charleston pattern with bass fills added:

Next, try alternating between different patterns, mixing long and short comps, and adding “push-offs,” moments where you repeat a chord on a consecutive downbeat and offbeat.

Bass in Left Hand

If you really want to imitate the sound of a full jazz rhythm section, there’s no substitute for playing a bassline. When you play a bassline, the left hand must remain dedicated to the bass while the right hand covers the chords and the melody.

There are three essential kinds of basslines in jazz. Great jazz bassists spend an entire lifetime mastering the creation of basslines, but I’ll give you some quick ideas here.

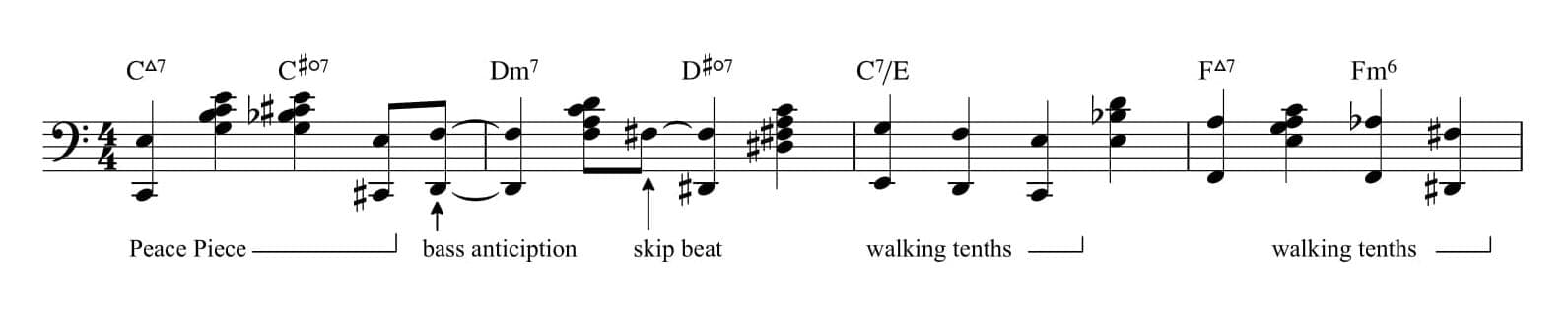

A bassline in two consists of two half notes per measure, and has a relaxed, “easy-going” feel. Most swing tunes start with a bassline in two. The easiest way to create a bassline in two is to place the root of the chord on the downbeat and another chord tone, usually the fifth or third, on beat three.

A bassline in four, or walking bass, consists of four quarter notes per measure. It generally has a more “driving” feel than a bassline in two. Creating a bassline in four is too intricate to describe here. A short summary is that you want to hit the root on beat one and connect by step using the appropriate scales (but there’s a whole lot more to it!).

But how is the right hand covering both the chords and the melody? There are three main ways:

- The right hand can “shuttle” back and forth between playing a melody and comping

2. The right hand can play a melody in the middle range that highlights the notes of the chords, thus filling in the harmony through single notes. Sometimes, pianists will add a second note to highlight a melody note, creating a two-note chord, or “dyad.”

3. The right hand can play the melody with the top of their hand and harmonize chords beneath the melody note.

Solo Jazz Piano – Leave Out The Bass

Lots of great pianists choose to simply leave out the bass for extended passages to highlight other musical elements. In this case, the right hand usually plays the melody and the left hand plays the chords, or both hands share the chords.

The simplest way to leave out the bass is to simply use the left hand to play chords in the middle range of the piano while the right hand plays the melody. Bill Evans does this all the time when he improvises and it sounds great!

Another interesting way to play without the bass is to use voicings that harmonize the melody. These fall into two categories – tonal and modal.

TONAL MELODY HARMONIZATIONS

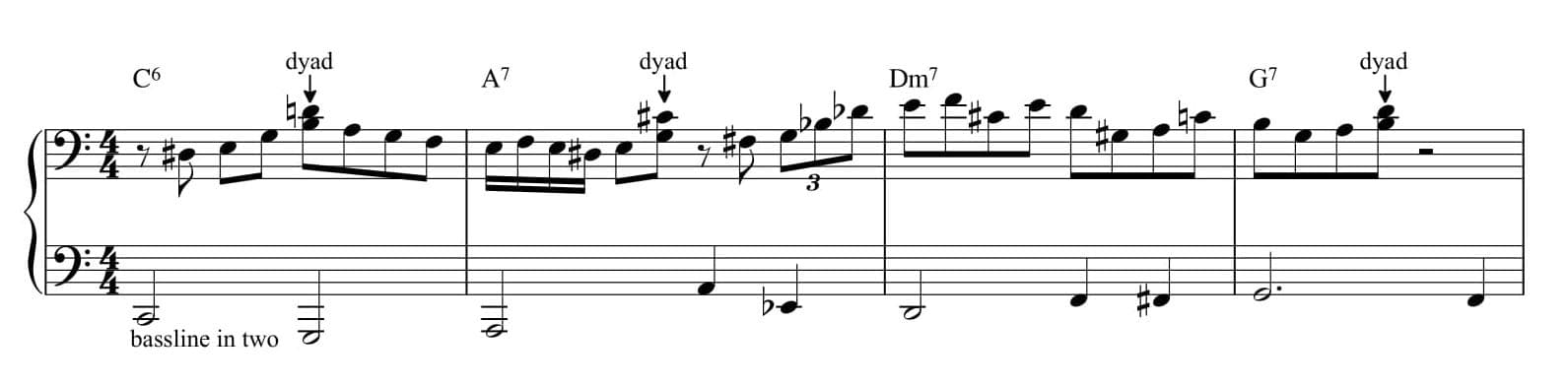

The two main ways we harmonize a melody with tonal voicings are with closed-position (“Shearing”) voicings and drop two voicings. These are complex artforms that take years to master, but I’ll give you the basics here.

A closed-position voicing has five notes, with an octave between the top and bottom note. Four of the notes are played with the right hand and one is played with the left hand. The key to making closed-position voicings sound great is that the left hand must connect the melody to give the illusion that both hands are moving smoothly. Closed-position voicings usually remind me of the big band era – they sound like a saxophone section tightly harmonized. They’re closely associated with the British jazz piano legend George Shearing who played them with great speed, style, and accuracy.

Drop two voicings have only four notes, usually with a tenth between the top and bottom note. The right hand plays three notes while the left hand plays only one, still very intentionally creating a legato connection. Drop two voicings generally sound lighter and more “modern” than closed-position voicings.

When playing both of these styles of voicings, the left hand frequently ornaments its single note melody with ghost notes, slides, turns, and scoops to simulate the expressiveness of a horn player, guitarist, or singer.

MODAL MELODY HARMONIZATIONS

Modal jazz is a style that rose to prominence in the 1960s, starting with Miles Davis’ album Kind of Blue. In modal jazz, the notes of the scale (or mode) are given equal importance, so it’s no longer as essential to highlight, say, the third and the seventh of each chord.

There are two styles of modal voicings that every pianist should know – So What and Quartal. A So What voicing consists of five notes, all arranged in fourths except with a third on top. A quartal voicing consists of notes all arranged in fourths. Quartal voicings can be as many as six notes, as played by McCoy Tyner, but to harmonize melodies, four or five notes is usually the appropriate size.

The following passage presents the melnody of the folk song “Danny Boy,” mixing between So What and Quartal voicings:

SHARED HANDS VOICINGS

For shared-hands voicings, the right hand plays the melody, the left hand plays the bass, and the two hands share the midrange chords. Although it oversimplifies the concept, it is useful to think about the third, fourth, and fifth fingers of the right hand as dedicated to the melody, the third, fourth, and fifth fingers of the left hand as dedicated to the bass, and the thumbs and index fingers of both hands as dedicated to the chords.

Unfortunately, there isn’t a simple formula for shared-hand voicings because they are dependent on the range and pitch content of the melody. In my book, I have two whole chapters that give rules, examples, and tips about how to come up with the absolute best shared-hands voicings for different types of chords. But here’s a quick summary:

- Include the third and seventh

- Don’t double notes (that is, use only one “C,” only one “F”)

- Space your voicing fairly evenly

- Avoid minor ninths, the interval of an octave plus a half-step

Here’s a passage from the song “Danny Boy,” arranged with shared-hands voicings. I’ve put the melody on a separate line so the voicings can be read clearly.

One of my favorite ways to use these voicings is in what I call a “repeated quarter-note ballad.” In this style, one note from each voicing, typically the thumb of the left hand, is repeated in quarter notes to act as the timekeeper below the melody. This simple repeated note creates just enough rhythmic movement to make the melody and chords sound like a full arrangement. Here’s that same passage from “Danny Boy” presented with repeated quarter notes. Note that when the chords change every beat, no extra quarter note is needed.

Conclusion

Those are the five principal ways that pianists manage the dilemma of playing three parts with two hands. There are a lot more details and tons more fun stuff in my book, Playing Solo Jazz Piano ($15 for PDF / $20 for signed hard copy). It covers topics like reharmonization, taking inspiration from classical music, perpetual motion à la Brad Mehldau, Latin styles like bossa nova, mirror piano, rubato ballads, pedalling tricks, counterpoint, and much more.

Blog written by Jeremy Siskind

PWJ Courses to further explore Solo Jazz Piano Playing include:

► Cycle of Fifths in 3 Jazz Styles:

► 6 Jazz Ballad Harmonic Approaches:

► Ode to Joy in 3 Jazz Styles:

More Free Lessons

Learn to play piano like a pro on Dizzy Gillespie's iconic bebop tune "A Night in Tunisia," mastering the chords and feel from the lead sheet.

Struggling to play blues piano with skill and sensitivity? Master these blues piano left hand patterns to take your feel to the next level!

Some jazz standards like “On Green Dolphin Street” mix Latin and swing within the same song…Learn how to master these “transition tunes.”

Looking for downloads?

Subscribe to a membership plan for full access to this Quick Tip's sheet music and backing tracks!

Join Us

Get instant access to this Quick Tip and other member features with a PWJ membership!

Guided Learning Tracks

View guided learning tracks for all music styles and skill levels

Progress Tracking

Complete lessons and courses as you track your learning progress

Downloadable Resources

Download Sheet Music and Backing Tracks

Community Forums

Engage with other PWJ members in our member-only community forums

Become a better piano player today. Try us out completely free for 14 days!